25°41'45.1"N 32°37'41.6"E

Teedie, age 14, sits on the deck of the Aboo Erdan, skinning a bird. The crew of the houseboat, on which his family is ascending the Nile, watches. They are puzzled by this strange boy, whose Christmas present, opened aboard, was a French pin-fire shotgun. Before that, Teedie had been skinning and preserving birds he bought in Egyptian markets. Now he can collect his own.

Teedie has been an aspiring naturalist from his earliest days. A skinny, asthmatic, near-sighted child, he's determined to surmount his weaknesses by living a vigorous life. His passion for taxidermy is topped only by his passion for recording observations in his copious notebooks.

He attaches a "Roosevelt Museum" label to the bird's frail leg. This institution is an upstairs bookcase in his wealthy family's brownstone on East 20th Street. Soon it will move to the family's new mansion on 57th Street. But eventually, the Egyptian specimens collected by Teedie Roosevelt will end up in an institution co-founded not--as many people believe--by him, but by his father: the American Museum of Natural History.

47°14'11.5"N 103°37'39.7"W

The light has left Theodore's life. His beloved wife Alice, whom he married shortly after graduating Harvard, died of kidney disease a few weeks after giving birth to their daughter. His mother died on the same day. Forget his sprawling new home on Long Island. Forget his rising career as a reform-minded New York Assemblyman. Forget his baby girl, left with his sister. He has come to the rugged Badlands to start a new life and heal his broken heart.

Formerly he has been a visitor in the Dakota Territory. He claims to be part Westerner because he has an investment cattle ranch near Medora, managed by other men. Now he will build and run his own ranch, Elkhorn. For the next two years, he wears buckskins, chases cattle rustlers, kills elk, pronghorns, and jackrabbits. Some of the local guides find him absurd with his Daniel Boone costume and his Tiffany knife. Not a great shot, he has a silly habit of dancing around when he bags his game. He can name every bird but doesn't know that the Badlands are lousy cattle country. But the locals don't reckon on Theodore's writing skill. He has already published a history of the War of 1812. Now he starts writing memoirs of western life. On the page, he will earn the name of cowboy.

20°01'14.6"N 75°47'57.7"W

Colonel Roosevelt rallies his men. On horseback, a prime target for the Spanish, he exhorts them to move up Kettle Hill. The Spanish, he has assured them with racist élan, are a lesser race, sure to be overrun by their detachment's Anglo-Saxon vigor. Never mind that the Rough Riders, recruited on the frontier, are a mix of cowboys, Indians, and Mexicans--plus the occasional Eastern "dude." The soldiers obey, wading towards their target through waist-high water. Guns held to their chests, they march up the hill in a blue line. The Spanish blast away at them. Soldiers pitch forward and vanish but the mass moves up like a rising tide.

The consensus in Washington: Roosevelt is mad. Resigning as assistant secretary of the navy to lead a bunch of frontiersmen into battle, he has left behind his second wife, Edith, and five children. Once again, the skeptics fail to factor in Roosevelt's potent combination of energy, luck, skill, charisma, and self-promotion. He and the Rough Riders take Kettle Hill. With the help of other regiments, including African Americans, they win San Juan Hill. When Colonel Roosevelt returns from Cuba, he is more famous than the man who sent him there, President McKinley.

41°52'51.1"N 87°37'51.1"W

Governor Theodore Roosevelt is cheered enthusiastically as he rises to speak at Chicago's Hamilton Club. "I wish to preach," he tells them, "the doctrine of the strenuous life . . . that highest form of success which comes to the man who does not shrink from danger, from hardship, or from bitter toil."

He's not talking about herding cattle, or stalking big game, or charging uphill in a rain of shrapnel. The New York governor is talking about politics. Swept into the governorship after his Cuban exploits, he now wars against the spoils system, against low wages and poor labor conditions, against shabby salaries for teachers and segregated education. And he has added nearly 70,000 acres to the state's forest reserves. He has done all this believing it necessary to mediate the growing rift between capital and labor, between rapacious plutocrats and wild anarchists. People say he's a radical.

"I am a radical," he replies, "who most earnestly desires the radical program to be carried out by conservatives."

39°59'54.3"N 107°38'35.7"W (or thereabouts)

Vice-president-elect Roosevelt peers over the cliff's rim. He can't see the cougar, but the dogs are still baying. They trailed it for three miles and now the cat has hidden itself on a ledge they can't reach. Theodore summons Goff, owner of the dogs, and gets him to hold his legs. He scoots forward until his head, shoulders, and arms hang over the edge of the cliff. He sees the cougar. He shoots it between the ears.

He and Goff will shoot fourteen cougars on this trip, sending their skulls to C. Hart Merriam of the Biological Survey. The goal is to help catalog and classify the mammals of the United States. Cougars kill lambs, colts, and calves, so no one criticizes this slaughter. Besides, Theodore needs one last wilderness jaunt before settling into his boring new job as vice president--a post he earned when the New York party machine, sick of his reformist ways, decided to kick him upstairs.

The moon is shining over the snow-covered valley as they ride back to the Meeker ranch. It is, Roosevelt writes, "a white wonderland of shimmering light and beauty."

44°06'24.8"N 73°56'09.0"W

On the shore of Lake Tear of the Clouds, high on Mount Marcy, vice president Roosevelt eats a sandwich. Edith and the kids have turned back, but he's headed for the summit. He's been mountaineering for days, since returning from Buffalo, where President McKinley was shot by an anarchist. With the president now recovering, Roosevelt is back on vacation. He loves the Adirondacks. Trips there helped him overcome his childhood asthma.

Someone is panting now in an asthmatic way. TR looks up. It's a local man waving a telegram.

"The president . . ." he gasps.

32°42'18.1"N 90°55'42.6"W

The 235-pound bear is tied to a tree outside Onward, Mississippi. Stunned, it groans for air. The president's guides want him to shoot it. He's there to hunt bear, and he hasn't found any. But TR turns from the roped bear in disgust. To shoot it wouldn't be sporting. The incident will soon be trumpeted in newspapers throughout the nation. The bear is transformed to a cub. An enterprising stuffed-toy-maker even starts selling what he calls "Teddy's bears."

The story, one of the most famous about TR, skips why he was hunting in the South. In his first year as president, TR invited Booker T. Washington to the White House to discuss African American education. When it grew late, the president invited Washington to join him and Edith for dinner. On reports that a black man had dined at the White House, with the first lady present, the Southern press went bonkers. Newspapers went insane with racism. Disgusted and defiant, TR planned a hunting trip in the deep South. The leader of the hunt was Holt Collier, a former slave, and former Confederate soldier. In depictions of the hunt, however, Collier will be drawn as white.

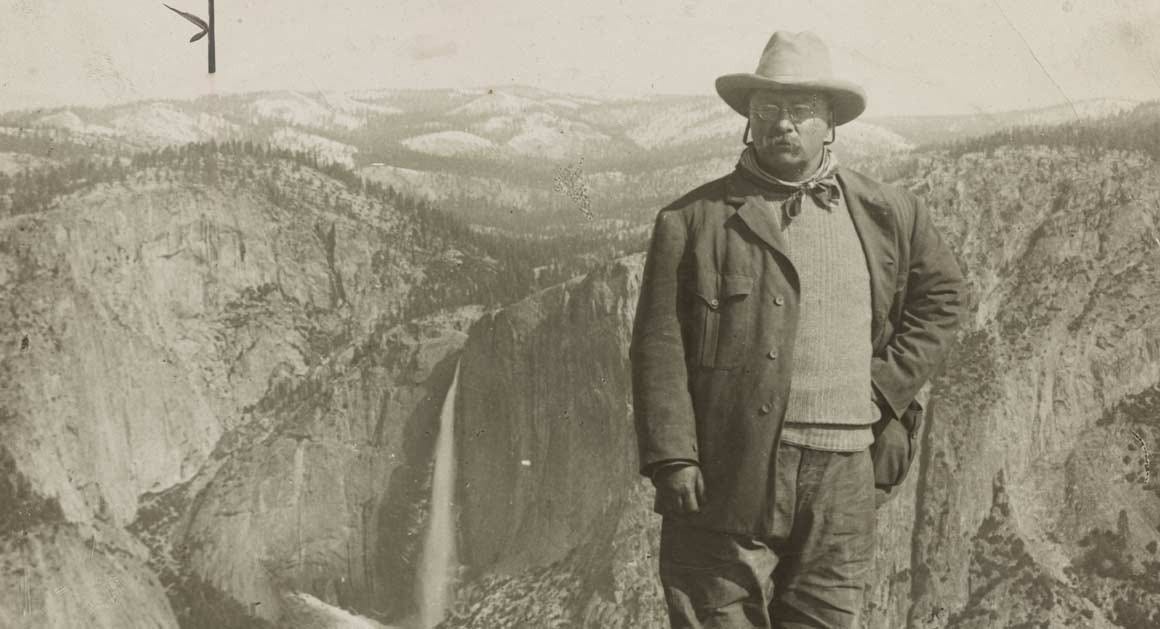

44°53'38.7"N 110°23'09.0"W (or thereabouts)

John Burroughs spurs his horse. The president is way ahead of him. The famous nature writer and the president have been camping in Yellowstone for three glorious days, free of journalists, fans, and Secret Service men. They have tracked bighorns and trailed birds--just that morning TR saw his first pygmy owl. Now he is pursuing a herd of elk up a mountain.

Burroughs has met TR, but on this jaunt, he is getting to know him.

"The President unites in himself powers and qualities that rarely go together," he will write. "He can stand calm and unflinching in the path of a charging grizzly, and he can confront with equal coolness and determination the predaceous corporations and money powers of the country."

President Roosevelt has taken on the railroads in the Northern Securities antitrust case, established the Department of Commerce and Labor, and resolved a coal strike by forcing both sides into arbitration. He has infuriated Western mining and timber interests by adding thousands of new acres to the nation's forest reserves, and even alienated some in his own party by advocating civil service reform. The robber barons who gave money to his campaign, thinking him one of their own, are outraged. As Henry Clay Frick growled, "We bought the son of a bitch, and then he did not stay bought."

Now this fearsome reformer is dashing up a mountain in pursuit of a few thousand elk, even though, for publicity's sake, he has no gun. Unlike some people, John Burroughs doesn't deplore TR's obsession with shooting animals, doesn't call him a "game butcher." Not that he buys the president's vision of a Daniel Boone myth as the American ideal. But it has the advantage of being easy to understand, unmarred by complexity or ambivalence. And like many folks, Burroughs just can't resist the man.

Finally, the exhausted elk stop, their tongues lolling, and the president catches up with them. He laughs, Burroughs writes "like a boy."

37°43'24.4"N 119°35'02.7"W

John Muir builds a campfire. He and TR have hiked through a snowstorm to get to Sentinel Dome. It's their second evening together. With an impish urge to make an impression, Muir takes a branch from the fire and puts it to a dead pine tree. The pine explodes in flames like a torch, and the California naturalist dances a jig around it. Delighted, TR joins him, dancing and shouting "Hurrah!"

Muir wants President Roosevelt to add Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa redwood grove to Yosemite National Park. TR is easily convinced. Leaving Yosemite, he will start the ball rolling, and eventually it will happen. Though later in his administration, TR will side against Muir and approve Gifford Pinchot's plan to dam Hetch Hetchy Valley, also in Yosemite, to provide water for San Francisco. The president wants to have his wild West and improve it too. John Muir will die despairing of this defeat.

46°35'33.3"N 120°33'06.2"W

The apples are wrapped in paper printed with "Yakima Valley Apples, Grown by Irrigation." No president has ever visited the Yakima Valley before, and apples are just one of the tributes grateful residents have prepared for TR. For he helped push the Irrigation Act, promising federal funding to make the dry West bloom, to build dams and store water in giant reservoirs, to create with irrigation a new Western economy built on tax-funded water. This will not be called an "entitlement" or "welfare" but rather "reclamation," as if it were not an exercise in ecological socialism but rather a simple redemption of God's original promise: Eden restored in the desert--with federal dollars.

As his open carriage rolls through the streets, the crowd shouts "Cowboy president" and "Hero of San Juan Hill." For they see in this eastern child of privilege, this radical progressive, this man who will tax the rich to water their orchards, a reflection of their own liberty-loving, anti-government independence. They see in him the spirit of the West.

8°55'50.6"N 79°33'24.9"W

President Roosevelt sits in the Bucyrus steam shovel. Delightedly, he pulls levers and watches the machine dip its trunk, like a prehistoric mammoth. Only recently he had jealously watched his sons play in a sandbox from a White House window, calling it "a heavenly place for two little boys." Now he has his own sandbox to play in: Culebra Cut on the in-progress Panama Canal.

Forget the whining of the anti-imperialists: TR expects the canal to be his greatest achievement. A French company mucked around on the isthmus for two decades with little to show for it but tropical diseases. They wanted to sell. But the Colombians refused to ratify a treaty letting the U.S. build and administer the canal. Roosevelt claimed no involvement in an incipient Panama separatist movement while moving American navy ships to the region. The Panamanians got the hint and declared independence. With almost comic haste, Roosevelt recognized the new nation and presented it with a canal treaty.

TR sums up his foreign policy simplistically: behave like an honorable man. Make no promises you don't keep, no threat you don't carry out. Stand up to the strong and treat the weak with justice and forbearance. None of that really justifies separating Panama from Colombia, but the canal, TR claims, is in the interest of "the civilized world." Secretary of War Taft, who is managing the project, is similarly dismissive, calling Panama "a kind of Opera Bouffe republic and nation."

Now TR is visiting to see the progress on "the big ditch." He enjoys seeing the machinery and the construction, but a letter to his son reveals his real interest. Panama, he writes, "is a real tropic forest, palms and bananas, breadfruit trees, bamboos, lofty ceibas, and gorgeous butterflies and brilliant colored birds fluttering among the orchids. . . . I would have given a good deal to have stayed and tried to collect specimens."

37°50'59.1"N 78°31'30.5"W

Near Pine Knot, his cabin in Virginia, TR watches some birds. There are about twelve of them, clearly pigeons, for they glide and land like pigeons. They have pointed tails and reddish brown breasts. Can they actually be passenger pigeons? The last documented sighting was seven years ago, in 1900. The bird--once known to darken the skies with its flocks--is now on the brink of extinction.

What grace offers him this gift? Could it be that some higher power approves of his effort, in his last two years in office, to make the Republicans the party of progressive reform? Approves of his pushing for national regulation of interstate corporations, an inheritance tax, an income tax, securities regulation, an 8-hour workday, workman's compensation, regulation of the stock market?

Is it a sign that he is succeeding in his quest to rebuild the mythic America he adores, putting buffalo back on the plains and bringing water to the West and maintaining the elk and deer by shooting their predators and encouraging every American to embrace the rugged individualism he stands for? Is it a sign that he will achieve his goal of making America resemble a painting by Frederic Remington (if you pay no attention to the federal man behind the curtain)?

Or is it, rather, gratitude for his conservationism, for facing down timber companies, mining companies, Western developers? For signing the Antiquities Act of 1906 granting him executive power to declare National Monuments with the stroke of pen? Are these birds a mystic thank-you for a presidency that will ultimately put some 230 million acres of America under federal protection? That will create, along with 5 national parks and 18 national monuments, 51 federal bird reserves?

The only way to officially document the sighting is to shoot one. The birds rise from the pine tree and wheel in tight formation through the sky. The president stands still, watching.

26: Theodore Roosevelt