James Garfield worked hard. Born in an Ohio log cabin, he was the first in his family to go to college. He graduated Williams with honors and returned to Ohio to teach history, philosophy, literature, rhetoric, and mathematics. His party trick was to write Greek with one hand and simultaneously write Latin with the other.

He worked hard, but did he work as hard as Blanche K. Bruce, the former slave who was nominated to be his vice president? Bruce worked his way up from servitude to the Senate, becoming the first African American to finish his term there. Senator Bruce was not selected to be on his ticket, but Garfield appointed him register of the U.S. treasury. Bruce's was the first black man's signature to appear on the nation's money.

James Garfield was versatile. He even discovered a new proof of the Pythagorean Theorem. But was he as versatile as Harriet Wood, one of the women with whom he had an extramarital affair? Wood used the pseudonym Pauline Cushman, cross-dressed, and served as a Union spy, sneaking through Confederate lines to steal secrets until she was captured and sentenced to death. After Union troops sprang her, Garfield convinced Lincoln to confer on her the rank of major. Major Cushman went on the road, telling her tale at Barnum's American Museum.

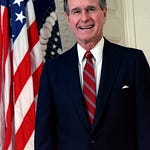

James Garfield was considered handsome. His good looks must have helped get him nominated, since almost no one knew who he was. But was he as handsome as his vice president, Chester Arthur? A man of many suits and few accomplishments, of luxuriant muttonchops and nary an elective office, Chet Arthur's claim to fame was being fired as collector of the New York Custom House. The position overflowed with bounties and kickbacks, keeping Arthur in the champagne and oysters he enjoyed. But President Hayes, determined to reform the spoils system, had sacked Arthur. Chet was nominated as Garfield's number two in deference to the Stalwarts, the Republican wing that opposed these very reforms.

James Garfield was an interesting man, but he was destined to be surrounded by people more interesting than he was. Yet he became the most interesting person in the nation after he was shot in the back in the Baltimore and Potomac depot. Garfield initially survived the shooting, and as he wavered between recovery and relapse, telegraphs clacked out his every up and down for newspapers across the nation. But even then, he was surrounded by what were arguably more interesting people: Charles Burleigh Purvis, a black doctor who attended to him at the station. Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, who became gloomy over the similarity to his own father's death. Susan Edson, the doctor of Garfield's wife Lucretia, who was part of his medical team at the White House. Alexander Graham Bell, who was summoned to find the bullet in the president with his new invention: an early version of the metal detector. It didn't work.

Also more interesting than Garfield, at least to us, is the person who shot him: Charles Guiteau, a man with a scraggly beard and crazy eyes, who had lurched through life as a failure at a long list of things. After failing to get into college, he joined the Oneida Community, a utopian religious commune with a policy of free love (and female pleasure) that scandalized the public. Guiteau failed there too: Oneida women kicked him out of so many bedrooms, he earned the nickname "Charles Gitout." Subsequently he failed to launch a newspaper, failed to practice law, failed at marriage, and failed to become a preacher. He published a book that he failed to write himself. His father thought he was possessed by the devil; his brother thought he'd gone mad from masturbating too much.

Guiteau's latest failure was politics. Hanging around hotel lobbies and public buildings, he generally made himself annoying by repeatedly asking for choice appointments, like minister to Austria or France. He was seen as a bore and a nutter. A Stalwart, Guiteau decided to execute Garfield so that Chester Arthur would become president. Charles figured Chet, who'd been distantly polite to him, would give him the kind of post he deserved. He stalked Garfield for days, and finally shot him as he passed through the ladies' waiting room at the train depot. "My God, what is this?" Garfield cried as he fell to the floor. The ladies' waiting room attendant rushed to his side and cradled his head. Guiteau was immediately apprehended, declaring "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts--Arthur is president now!" On his person, police found several letters confessing to the crime, including one addressed to Arthur in which he offered suggestions for Cabinet appointments.

James Garfield was stoic. Was he as stoic as his wife Lucretia, who had forgiven him his multiple affairs, and now nursed him through a slow death from sepsis? His doctors, no fans of the new germ theory of disease, insisted on repeatedly probing his wound with dirty fingers. They lanced the pus-filled entry point with dirty tools. When he lost his appetite, they subjected him to enemas of egg yolks, beef broth, and animal blood. He became emaciated, and feverish, but he didn't complain. Nor did Lucretia bewail her fate when her husband lapsed into unconsciousness and died. He had been president for about six months, almost half of it incapacitated.

Chester Arthur was not a particularly interesting man. But he became more interesting as a result of Garfield's assassination. As the president lay dying, Arthur went into hiding, his distress obvious to all who saw him. Chet had been fine with the idea of being vice president, a largely ceremonial position that would have given him an excuse to buy flashy suits and throw big parties at his townhouse in New York. But he didn't want to be president. "God knows I do not want the place I was never elected to," he declared to the Cabinet as the president lay dying.

Even worse, once newspapers published Guiteau's claim that he had assassinated Garfield for Arthur, many people wanted Chet dead. Threats poured in. Birthers started insisting that Arthur was ineligible to be president because his father hadn't been a citizen when Chet was born. When that was debunked, they claimed he was actually Canadian. Throughout all of it, Arthur laid low and prayed for Garfield's recovery. When the message finally came that Garfield was dead, everyone in Arthur's townhouse heard him shrieking and sobbing.

Upon taking office, Chet showed little interest in governing. He came to work late and left early. His lackeys gave him a pile of fake documents to carry around so he'd look busy. A widower, he took on the tasks a First Lady might have assumed: he renovated the White House. He replaced old and shabby furniture. He installed Tiffany glass and the building's first elevator. He had a ridiculously opulent new carriage made for himself. He threw elegant parties. Rutherford Hayes summed up the Arthur presidency as "liquor, snobbery, and rosé."

Chester Arthur was less interesting than Garfield, but like him, he was bound to be overshadowed by the interesting people around him. One of them was Julia Sand, a 31-year-old New York invalid with a fierce interest in politics. Her first letter to Arthur arrived as President Garfield was fighting for his life. In it, she urged Chet to rise to the occasion. "If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine," she told him. "Reform! Rise to the emergency. Disappoint our fears."

Sand's letters, alternately goading, flattering, and berating, came regularly. She told the president to steer clear of General Grant, to avoid appeasing the South, to veto the first Chinese Exclusion Act, and to get on board with civil service reform. Surprising everyone, Arthur did all of these things. Sand was not alone in calling for civil service reform. A disappointed office-seeker had just murdered a president: the nation was demanding an end to the spoils system. Arthur's signing of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act, requiring civil servants to be chosen by merit instead of political loyalty, was particularly galling to his former cronies. It was his most significant accomplishment. The most interesting thing he did may have been at the instigation of an invalid woman he knew only through letters. In 1882, he appeared at her New York home unannounced and chatted for half an hour.

What was the president's purpose in seeing Julia Sand? Did he hope to meet a potential wife? Did he feel obliged to her for her advice? Was it interest or mere curiosity? Whatever it was, his visit resolved it. He never saw her again, never responded to her subsequent letters. Chester Arthur turned out to be a more interesting president than anyone had expected, so much so that at the end of his term, his friends urged him to run for office again. But Chet had already been diagnosed with the Bright's disease that would kill him. The presidency? He wasn't really interested.

Share this post