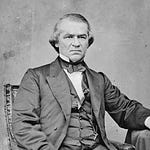

He beat the incumbent in 1888, but he lost to the same guy when they faced off again in 1892. He was the more effective president, but he couldn't convince people of the fact.

The great-grandson of a founding father and the grandson of President William Henry Harrison, Benjamin Harrison once started a speech "I am the grandson of nobody." He thought he should stand on his own two legs. Besides, despite his impressive ancestry, his upbringing was humble. Born to an Ohio farmer father, schooled in a log cabin, he was an example of the hard work and individual striving he valued. But he couldn't convince people of the fact. He battled the false perception that he hailed from the kid-gloves class.

He did have a certain stiffness that came from his deeply held faith. There was a moralistic side to him: he refused to play the patronage game, and he won several enemies for every post he filled. He wasn't a people-pleaser; undemonstrative, he came across as austere, even icy. In actuality he was warm with his children and loving towards his wife. But he couldn't convince people of the fact. Many found him unlikeable.

Nor could he convince the public of the fact that he was a moderate. This was because he got things done. Voted into office along with a Republican Congress, he was able to put his views into action. His first address to Congress laid out a bold legislative roadmap: revise the tariff, strengthen the currency, break up trusts, pass regulations to protect workers, increase veterans' pensions, support education, fund internal improvements, rebuild the navy, and protect the voting rights of black Americans in the South. The Democrats hated this last issue in particular, seeing in it a return to the bad old days of Reconstruction, when the federal government tried to make them let black people vote. They called it the "force bill."

The first session of Congress under Harrison's administration was one of the most legislatively productive in history. He signed antitrust legislation, a veteran pension bill, legislation allowing the USDA to employ meat inspectors, legislation establishing government support for the overseas mail, legislation that created National Forests. The opposition turned every fact to a liability, squawking about overspending, about inflation, about an activist Congress stepping on their cherished states' rights. They used filibusters and other procedural tricks to block the president's actions.

When the money market tightened, Harrison helped avert a financial panic by injecting Treasury funds into the economy. Under his administration, the economy was strong, but he couldn't convince people of the fact. The Democrats blasted him for inflation; they denounced the tariff; they claimed he was in the pocket of Wall Street. In the midterm elections, Republicans lost their majority in the House.

Faced with a solid opposition and an obstructionist attitude in Congress, he turned his attention in the second half of his term to foreign policy. He upheld the Monroe doctrine policy of American dominance in its own hemisphere. He rebuilt the navy. He hashed out international trade agreements, working to open foreign markets to American products. He thought this would be good for both American manufacturers and American labor, but he couldn't convince people of the fact. When strikes broke out in multiple industries--ironworkers, railroad workers, coal miners--he refused to send federal troops to put them down, insisting it would only cause more violence. Only after the Idaho governor, faced with striking silver miners, declared he could no longer keep order did Harrison send in troops. Democrats used this to claim he was anti-labor.

He continued to push for civil rights legislation, but it was here where he made the least progress. He wanted the federal government to spend money on education for former slaves. He supported legislation to protect black voting rights in the South. He endorsed passing a constitutional amendment codifying civil rights legislation the Supreme Court had declared unconstitutional in 1883. None of these things came to pass. He believed that denying black people civil rights hurt everyone, but he couldn't convince people of the fact. "The colored people did not intrude themselves upon us;" he declared in frustration; "they were brought here in chains and held in communities where they are now chiefly bound by a cruel slave code . . . When and under what conditions is the black man to have a free ballot? When is he in fact to have those full civil rights which have so long been his in law?"

Although he was re-nominated, his own party failed to fully back him. "A certain wing of the Republican party was not sincere in its support of the President," one analyst wrote. "To his face they were pleasant, but when absent, acted like Judas." This may have cost him the election. Or perhaps Grover Cleveland won again because the opposition could tar Harrison with the brush of class resentment, claiming that his economic policies benefited Wall Street alone. "The workingman declined to walk under the protective umbrella," Harrison mused, "because it sheltered his employer also. He has smashed it for the fun of seeing the silk stockings take rain."

Harrison firmly believed that government could help people. He thought the purpose of American institutions was to give the common worker a chance at bettering his own prospects and those of his children. He believed that was America's purpose. But he couldn't convince people of the fact. And so he became the first--and so far only--president to beat an incumbent and then lose to him in a rematch.

Then again, perhaps the issue wasn't that he couldn't convince people of the facts. Perhaps it was simply that the facts didn't matter. Later in life, considering why he lost to his predecessor, Benjamin Harrison offered a simpler explanation: "The working men voted their prejudices."

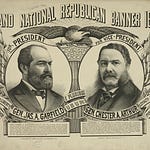

23: Benjamin Harrison