Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, 1921-1930

It was all I ever wanted, and I wanted it all my life--to be on the Supreme Court. I love the law, always have. The law is reason, pure and simple, drained of emotion and free from all political considerations. The courts are, rightly, a conservative force. They help slow the headlong transformation of society desired by progressives, anarchists, and Bolsheviks. The courts in my day slowed the antitrust impulse, siding with corporations by granting them rights as "people" and slowing the pace of racial reform. Why remake society so quickly that people can't keep up? My Supreme Court overturned taxes meant to punish corporations for using child labor, upheld an anarchist's criminal conviction for advocating the overthrow of the government, struck down states' ability to ban private or religious schools, and allowed state schools to segregate not only African Americans, but people of Chinese origin.

I was never as happy as I was as Chief Justice.

Federal Judge of the Sixth Circuit, 1892-1900

This was meant to be a lifetime appointment, and my plan was to stay a circuit judge until I was raised to the Supreme Court. The Sixth Circuit comprised Ohio, Michigan, Kentucky, and Tennessee. I was known as an "injunction judge"--that means I was willing to throw labor organizers in jail if they were causing trouble. And why not? Some of them are just anarchists. And sometimes I sided with labor--but only if the legal case was there. The law has no politics. That's what I love about it.

When I was called by McKinley to Washington and offered the position of president of the Philippine Commission, I agonized over whether to take it. "I confess that I love my present position," I wrote to my brother. "Perhaps it is the comfort and dignity and power without worry I like."

Honestly, being on the Federal circuit was almost as good as being on the Supreme Court.

Judge on the Superior Court of Ohio, 1887-1890

This job I also enjoyed, though it didn't bring as much power as being on the federal circuit. But power was never really my thing. And even though it was just routine, boring cases, I found it satisfying. Staying up late, reading precedents, putting a legal argument together piece by piece. That's how my mind works.

Solicitor General of the United States, 1890-1892

There was this: it made Nellie happy. My wife Nellie was ambitious--I always said she was the superior intellect and the "senior partner" in our alliance--and my taking this position put us in good standing in Washington society. We could hang out with Senators and Cabinet members and foreign dignitaries and the like. Personally, I preferred hanging out with Supreme Court justices and talking law, but we met many highly placed political figures when I was Solicitor General, and this pleased Nellie.

Oh, and I won the vast majority of the cases I brought on behalf of the government so there's that.

Professor of Law, Yale University, 1913-1921

Sure, it was nice to go back to my alma mater as a professor, and the students gave me a warm welcome. After all, I was the ex-President. But teaching was never really my main thing, and although I hoped to preach the gospel of "constitutionalism and international peace," I'm not sure the undergraduates got the point. And from my post at Yale, I had a front-row seat for all the politics still unfolding in Washington--TR and his possible future run for president, Wilson and his undistinguished Supreme Court appointments.

On the up side, the combination of being an ex-President and a Yale professor meant I could bolster the household economics by taking gigs as a lecturer-- for up to $1000 per appearance. I added substantially to our nest egg in these years.

President of the Philippine Commission/Civil Governor of the Philippines, 1900-1903

The U.S. never should have gotten mixed up in the Philippines in the first place. That's what I told President McKinley when he proposed sending me there to administer the protectorate. I hoped this would persuade the president that I was the wrong guy for the job, but for some reason, it didn't. And then the president did the one thing that always got my compliance: he promised to appoint me to the Supreme Court later if I would take the post.

And so I found myself sweating it out in the tremendous heat and humidity of this island nation, learning more than I'd ever cared to know about sanitation, education, roads, currency, and the civil service. I was immediately plunged into a constant struggle with the military brass, because they were interested mainly in using martial law to keep the natives in line. I was distressed to see the behavior of the American military troops. The foot soldiers were constituted of the "rag tag and bob tail of Americans who are not only vicious but stupid." They had a tendency to boss around the natives when they weren't treating them to the "water cure," a particularly painful form of torture.

As I saw it, the long-term goal was making the Philippines fit for self-government. I despaired of it happening soon. Corrupted by a long period of crooked Spanish rule, their culture was rife with gambling, bribery, and prostitution. It was difficult to find "not honest Americans, but honest Americans who will not become dishonest under the temptations."

It didn't make me love this post any more when I had a bout of amoebic dysentery so severe I had to return home for multiple surgeries. Or that several Supreme Court vacancies came and went that TR--now president-- offered me and that I felt I couldn't accept with my job still incomplete in Southeast Asia.

Secretary of War of the United States, 1904-1908

The worst of it was that the Cabinet meetings were mostly about politics. I told Nellie that after my first day, reminding her that "politics, when I am in it, makes me sick." But Nellie was pleased about this job too, because an important Cabinet position was clearly a stepping stone to the presidency. And she wanted that for me, no matter how much I told her I didn't want it for myself.

As Secretary of War, I did get to stay on top of the Philippine situation. TR put me in charge of the Panama Canal project. But for the most part, TR was his own Secretary of War, just as he was his own Secretary of State. I walked to work every day, and went on a strict diet under which I lost 76 pounds. All my suits had to be re-tailored. So you can say I made good use of that job, even though I hated every minute of it.

President of the United States, 1909-1913

I never wanted to be president. I called the job a "nightmare." I ran an uninspiring campaign, despite TR's relentless coaching, encouraging me to get rough with my opponent, William Jennings Bryan. A Harper's cartoon depicted TR as a volcano, spewing forth a plume of ash that almost obscured my face. Wags declared that "Taft" stood for "Take Advice From Theodore." When a blizzard struck on my inauguration day, I noted that "even the elements do protest."

Never mind that I actually brought more suits against corporations for antitrust activities than TR had. I was seen as a more conservative, less politically talented version of Roosevelt, and that's not totally unfair. I rolled back TR's racial reforms, vowing not to place African Americans in federal positions if it would lead to racial friction. I refused to take the kind of conservation action TR had, insisting that legislation was the better approach to saving wild lands. I fired Roosevelt's much-admired conservationist chief forester, Gifford Pinchot, when he objected to my opening Alaskan lands to mining and timbering.

Nellie had a stroke after my first year as president and to be honest, I was kind of distracted by taking care of her and teaching her to speak again. What's a presidency compared to real devotion?

And then, there was this irony: I had the opportunity to make six appointments to the Supreme Court, the very job I myself had always wanted. No president since George Washington had appointed that many justices. I chose good, conservative judges, and when the post of chief justice opened up, instead of giving it to the man I had quietly promised it to--a man who would quite likely outlive me--I elevated one of the court's older justices to the role. That way my own chance of getting the seat might still come to pass. As in fact, it did.

TR tried to remake the Republican party as the party of progressive reform. I brought it back to its roots as the party of stability and big business. It was almost a relief when TR ran against me for the Republican nomination, and failing to get it, ran a third-party campaign that divided the Republican vote and assured Democrat Woodrow Wilson an easy win. As I told the next president upon leaving the White House, "this is the loneliest place in the world."

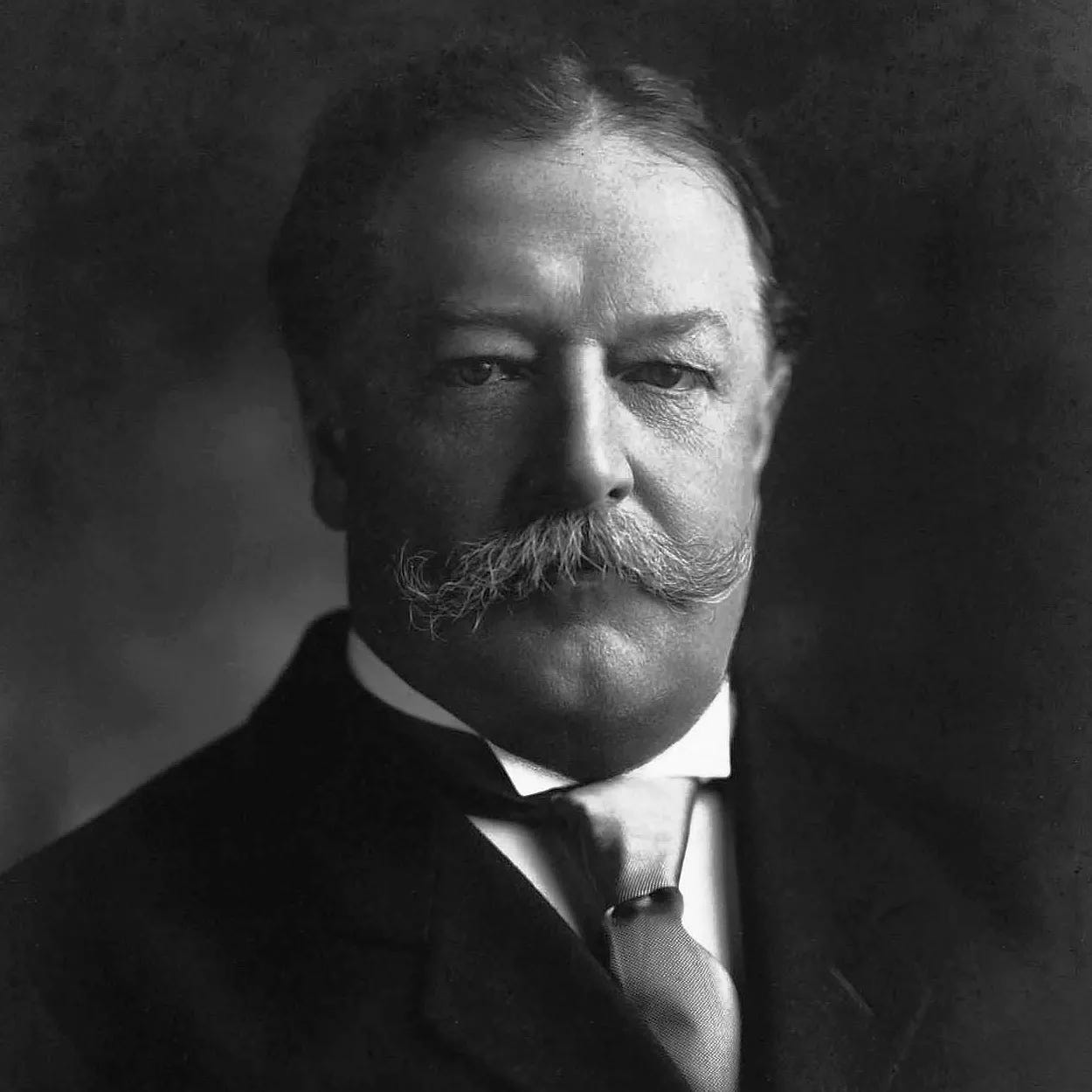

27: William Howard Taft