4: James Madison

The story of a sword

Where did he get the sword? Runty, bookish, skittish James Madison had never been in a battle. He hadn't even been abroad. Could he even hoist a sword? He was a man of the pen. But what a pen. His hand was in the Constitution and The Federalist; he singlehandedly wrote the Bill of Rights. Without his notes, history would know a lot less about the constitutional convention. Madison biographer Lynne Cheney, whose husband Dick Cheney was White House Chief of Staff under President Gerald Ford, called Madison "one of the great lawgivers of the world" and one of the "two greatest minds of the eighteenth century." (The other, she says, was Thomas Jefferson.)

Not a man of the sword. Yet as the British bore down on Washington, Madison's wife Dolley wrote her cousin that she was keeping "the old Tunisian sabre within my reach." Was it a ceremonial dress sword? Had it been a gift? When Madison was Secretary of State, the first Muslim ambassador to visit the U.S., Sidi Suliman Mellimelli, brought him some "souvenirs." President Jefferson had declared the Barbary States--Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and Morocco--to be sponsors of piracy, and refusing to pay their usual tribute, sent ships to blockade Tripoli. When the USS Constitution captured some Tunisian blockade-runners, Mellimelli was sent to negotiate their return.

Madison biographer Lynne Cheney, whose husband Dick Cheney was a member of Congress when President Reagan ordered air strikes on Tripoli without Congressional approval, writes that Madison was responsible for a key word change in the Constitution. He changed the line giving Congress the power to "make war" into the power to "declare war," thus ensuring for the President "the power to repel sudden attacks." Only Congress could declare war, but the President could make it unofficially--as Jefferson did in Tripoli. Cheney writes that the conflict ended when the United States launched "a land and sea assault on Tripoli aimed at replacing the pasha with his equally corrupt brother."

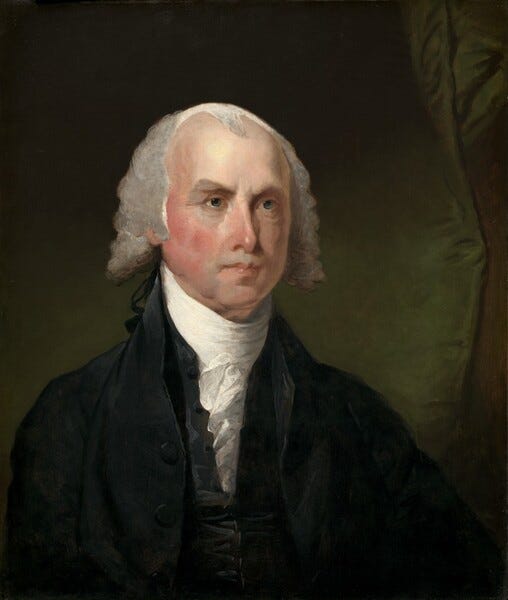

James Madison disliked wars. He felt that a republic should be careful to separate "the power of the sword from the purse." The judiciary's job was "to prevent an appeal to the sword." He had at least one portrait painted wearing a sword, as Washington often did, but mostly he was painted without it. He did not want to conflate executive power with warmaking. Yet he became the first American president officially to take the United States to war. In 1812, he convinced Congress to declare war on Britain. Right away, he made a misstep, one that future presidents would repeat: an unmilitary man, unblooded in battle, he donned a black hat with a ridiculous military cockade, and toured his Department of War.

It was an unpopular war, and, historians have concluded, a largely unnecessary one. Lynne Cheney, whose husband Dick Cheney, as Secretary of Defense, oversaw the first Iraq War, writes that Madison had "concluded that opposition to the war was not going to go away,” so he decided “'to throw forward the flag of the country, sure that the people would press onward and defend it.'"

It worked, in a partisan way. Democratic-Republicans scrambled to support their President's war, while the Federalists grumpily opposed it. Most Americans didn't understand why they were fighting. But once begun, war has a momentum of its own. Supporters claimed that it was unpatriotic not to fall in line with the president. "This [wartime] is no time for debating the propriety of a war," declared the Washington National Intelligencer.

The factionalism grew worse when it became apparent that Madison had misled Congress in urging war, sending them a dubious cache of letters he had purchased from a con man, allegedly showing that British secret agents were ginning up secessionism in New England. War hawks quickly claimed, without evidence, that the British were also inciting "savages" to attack Americans in the border regions along the Mississippi. Lynne Cheney, whose husband Dick Cheney, as vice-president, declared there was "no doubt" that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, who repeatedly alluded to a made-up connection between Saddam Hussein and the 9/11 hijackers, asserts that these letters "should have served as a warning about New England discontent and British willingness to take advantage of it, but events that had nothing to do with the substance of the letters largely obscured those messages."

Huh?

Never mind; Anglophobia was already ascendant. James Madison had the numbers to go to war. And so the Americans burned York (today's Toronto), and the British burned Washington. Dolley Madison oversaw the removal of many valuables, including state papers like the Declaration of Independence and Gilbert Stuart's portrait of President Washington, before she fled, just ahead of the British. Did she take the Tunisian sabre for self-defense? Or leave it? The British soldiers who arrived at the White House found the table set and dinner ready; they ate the president's duck and drank his Madeira. They donned his starched shirts and brandished his ceremonial sword. Then they piled up all the valuables and put them to the torch. It's possible the Tunisian sabre was in that bonfire. It's possible it was looted. At least one contemporary account says that a Scottish soldier named Beauchamp Colclough Urquhart came home with Madison's "dress sword" as a war souvenir. Requests for further information from his ancestral estate, Meldrum, have gone unanswered.

Like Washington and Jefferson, Madison was a slaveowner, and like them, he professed to hate slavery. Like them, he did nothing to end it. As the three-fifths compromise was being hammered out, Madison objected to the use of the term "slavery" in the Constitution. Lynne Cheney, whose husband Dick, as vice president, was behind George W. Bush's policy of allowing "enhanced interrogation" of terrorist suspects, contra the Geneva Convention banning torture, explains: "Euphemisms were a way of avoiding the terrible truth that slavery existed, but they also allowed the delegates to create a document suitable for a time when it would not."

James Madison invented the office of vice-president.

In old age Madison warned against war as "the true nurse of executive aggrandizement." War-- even a war on terror--was too easy a means for the president to consolidate power. And yet Madison is most remembered as the first commander-in-chief to command. The War of 1812, remembered today mainly as the inspiration for The Star Spangled Banner, was called in its own time Mr. Madison's War. "Perhaps only the Iraq War of the early twenty-first century has been more closely associated with a specific president," writes historian Michael Beschloss. He and others argue that James Madison opened to door for future presidents to wage unpopular, unnecessary wars that are supported by only one party.

In July, 2013, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement announced that they had discovered a ceremonial sword that was looted from Saddam Hussein's office ten years earlier. Considered an Iraqi cultural artifact, the sword was ordered returned.

Very interesting and well written! I especially appreciate the weaving of more recent history in with the older events. It provides invaluable context to current events. Thanks for sharing!

Well done on Madison.