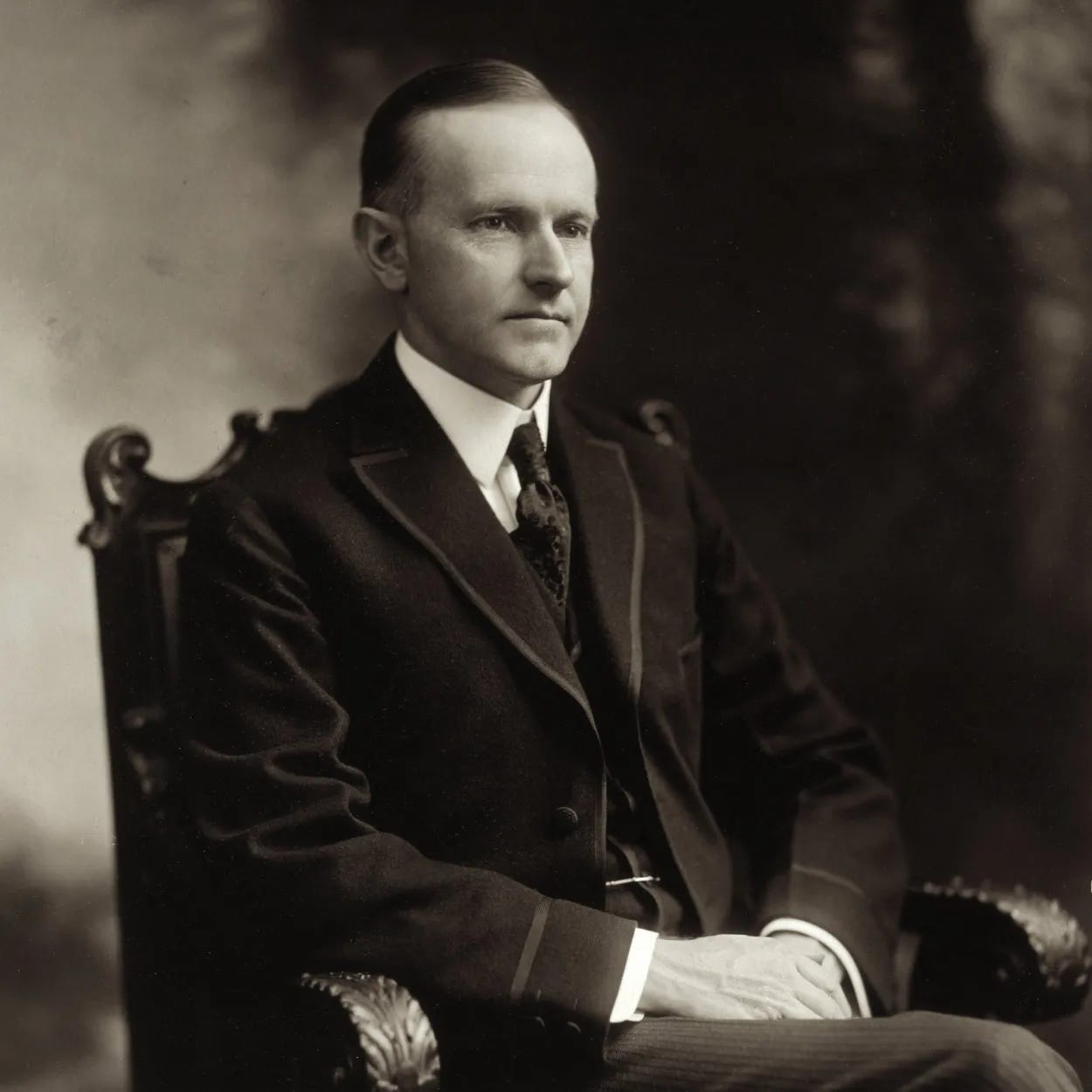

People were surprised when Calvin Coolidge came down hard on the Boston police strike. Born and raised in rural Vermont, the Massachusetts governor was a man of few words, so taciturn he earned the nickname Silent Cal. Now people saw him as a man of convictions, but what were those convictions, and how could they tell? He said nothing about his actions. Had he fired the police who walked off the job to strike a blow against labor? Or had his concern for public safety overcome his sympathy for the working man? Or, as a man who loved to delegate, had he simply followed the lead of his police commissioner? The terse telegram he sent to the president of the AFL made him nationally famous: "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time."

It could have been political suicide but in fact, the timing was perfect. Americans were sick of the labor unrest of the teens, and eager to get on with chasing postwar prosperity. They were poised to begin what Scott Fitzgerald called "the greatest, gaudiest spree in history." How could they tell what Calvin Coolidge stood for when he said so little, just things like "The business of America is business," and "The ideal of America is idealism"? It didn't matter really. The words sounded good: blandly optimistic, supervisory in a hands-off way, like "Boys will be boys." Without really knowing what he stood for, the Republicans nominated Coolidge as vice president and Americans voted him into office. The vice presidency was a dead-end job anyway, a sinecure with no real power. But then Warren G. Harding died unexpectedly of a heart attack and Silent Cal was elevated to the presidency. He got the news while visiting home in Vermont. His father swore him in at 2 am by the light of a kerosene lamp.

"I thought I could swing it," he later declared. Others were not so sure, and besides, how could they tell? Silent Cal had said so little and been so obscure as vice president that when the Willard Hotel, where he lived, was evacuated because of a fire, he was stopped and asked for ID on his way back in. "I'm the vice president," he said, and was asked: "Vice president of what?"

He retained a humility that was actually his most appealing trait. "While I felt qualified to serve," he wrote in his memoir, "I was also well aware that there were many others who were better qualified . . . When a man begins to feel that he is the only one who can lead in this republic, he is guilty of treason to the spirit of our institutions."

He retained his Puritanical morality. If President Harding was a speakeasy backroom, declared Alice Roosevelt Longworth, TR's gossipy daughter, then President Coolidge was a New England front parlor. Indeed, people saw the new president as old-fashioned, thrifty, and stoical, but were these his real qualities, and if so, how could they tell? The image of the president was shaped and molded to a great extent by a new type on the American scene, the publicity agent. A team of spin-doctors, promoters, admen, and filmmakers created the presidential avatar--a simple New England farm boy happy to roll up his sleeves and mend a fence when visiting his father in Vermont. Using photographs and newsreels and friendly newspaper editors, they sold Silent Cal with all the offhand slickness they might have used to sell the latest appliance or cigarette or breakfast cereal.

So he had a persona, but as president, Calvin Coolidge remained inscrutable. One might expect farmers to rally to him since he was the son of a farmer, but how could they tell? Again and again, he vetoed bills aimed at helping agriculture, a sector of the economy that was struggling in the otherwise roaring twenties. Calvin didn't think the government should be in the business of helping any one sector thrive. "Farmers never have made much money," said the farmer's son. "I do not believe we can do much about it."

Immigrants and African Americans might have offered him support, since he personally despised racial prejudice and felt that immigrants contributed to a stronger society, but how could they tell? He said little about it and his actions said something else entirely. "America must be kept American" he declared in his first State of the Union speech, and what that meant seemed clear when he signed an immigration bill meant to keep America white. It decreased the numbers of Jews, Slavs, Greeks, and Italians who were allowed into the nation, and when the Nazis came, those limits would consign millions of European Jews to death. The only part of the bill he seemed to regret was the part completely barring the Japanese. It was--though how could they tell--a misstep that would contribute to Japan's increasing militarization.

As for Mississippians wiped out by the Great Flood of 1927, he may have cared about them personally, but how could they tell? He said nothing about sympathy for them. He refused to visit the area and fought tooth and nail against letting the federal government get involved in flood relief. People should help themselves, he felt. Nor did he think the government should play a role in flood control--that job should be left to the states. Congress disagreed with him, and when they passed a relief bill without his support, he sullenly signed it in private, so that even when he could have taken credit for helping his citizens, no one could tell.

The centerpiece of his administration was the nation's booming economy, a phenomenon for which he was happy to take credit he didn't deserve. The "Coolidge prosperity," people called it. He put industrialist banker Andrew Mellon at the head of the Treasury and supported the millionaire's policy of laissez-faire. Their theory was that cutting taxes on the wealthy and corporations would cause profits to trickle down to the little man, and in the prosperous mid-twenties, it seemed to be working. Unemployment was down. Wages were stable. American business was on a spree, and the people happily joined in the fun. They were playing with fire, but how could they tell? They saw a skyrocketing stock market and an orgy of easy credit. Shoe shine boys offered stock tips with a five-cent polish; bell hops were buying land in Florida. Demand for stocks was so high the supply was challenged, and lower quality investments flooded the market, junk bonds and "preferred stocks" hawked by holding companies and investment trusts.

It had all the signs of a bubble, and it may be that Silent Cal saw the cataclysm looming. In 1928, he announced that he would not run for president again. "It is hazardous to attempt what we feel is beyond our strength to accomplish," he later explained. Did he know the coming years would collapse the bubble? Privately, he confessed that he thought Herbert Hoover, the new Republican candidate, would have a tough time of it. People speculated later that he had known an economic reckoning was in the offing, but how could they tell? He dutifully campaigned for Hoover. He said nothing about any warnings he was given. He expressed no anxiety about the future. He retired to Northampton and settled in to write his memoirs. Anodyne and sanctimonious, they read as if they were written by Chat GPT. They say surprisingly little about his actions, though they sometimes make a good case for his propensity to say nothing:

The words of the President have an enormous weight and ought not to be used indiscriminately. It would be exceedingly easy to set the country all by the ears and foment hatreds and jealousies, which, by destroying faith and confidence, would help nobody and harm everybody. The end would be the destruction of all progress.

When the Great Depression came, Silent Cal was perplexed and frustrated by the policies of the New Deal. He was a fish out of water, a relic of a former era. "I no longer fit in with these times," he told a reporter. But had he ever? His own administration had presided over a period of radical upheaval that seemed to wash over him without effect. Like some wax figure from Victorian times he had stood to one side and said nothing as modernity rushed in and changed the world. With his eyes fixed on an economy he saw as proof of his success, one wonders if he even knew what else had happened.

He died of a heart attack at home at the age of sixty. He said nothing, just fell to the floor of his dressing area. His wife found him lying on his back, silent forever.

Told that the former president had died, Algonquin wit Dorothy Parker had a typically quick riposte: "How could they tell?"

Share this post