Act I, Scene 2: a log cabin in Indiana, October, 1818

Nancy Lincoln moans in her bed. First she was listless; then she began to tremble. For a week now she has been retching. People call it the puking fever, milk sickness. They don't know yet that it comes from cows eating a poisonous midwestern plant called snakeroot. The cows rarely take sick, but folks who drink their milk do. Nancy doesn't know why, but she knows she is dying.

Her son Abraham, age nine, loves her. He has not yet heard the stories of her out-of-wedlock birth, the rumors of her own promiscuity, that will complicate her memory. He just knows that the mama who reads him scripture, teaches him letters, makes the squirrel dip and corn dodgers he loves, is fading away. His father, quick with the rod, will be all he has left--the father who hates to see him with a book when he could be wielding an axe. Abe doesn't know that a new mother, a stepmother, will save him. That she will convince his father to let him educate himself. Not knowing this, all he feels as his mother goes is howling horror, as if the life draining away is his own.

Act I, Scene 4: a meeting of the Young Men's Lyceum, Springfield, Illinois, January 1838

Abe Lincoln stands before the audience. He is 29, gangly, awkward in an ill-fitting suit. He is on his fifth attempt at a career, having worked as a ferryman, a store proprietor, a postmaster, a surveyor. Now he has been a state legislator for four years. When the legislature wasn't in session, he studied law, getting his license two years ago. He is known as a good debater, so the Lyceum invited him to speak. His theme is how United States political institutions can endure.

The nation is roiled by violence: mob lynchings in the South, violent crowds freeing fugitive slaves in the North. Lincoln doesn't condemn one side or the other. He calls out both for failing to trust in the rule of law. The nation is in danger, but not from an outside enemy.

"If destruction be our lot," he says, "we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide."

It's an interesting word. His friends sometimes fear that he himself will die by his own hand. They sat watch with him after his intended, Ann Rutledge, died. They have seen him through bouts of depression. He tells the audience there's only one way the nation can save itself.

"Reason," he tells them, "cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason—must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense.”

Act I, Scene 5: a barroom in Springfield, Illinois, sometime around 1838

People are talking politics. Abe is there, at the center. The conversation comes around, as it always does, to slavery. Lincoln says he dislikes slavery, but he believes the government can't ban it where it exists. Still, there should be no slavery in new states and territories.

Someone asks him point blank if he's an abolitionist. Lincoln is standing near Thomas Alsopp, whose antislavery views are well known. Abe reaches over and drops a hand on Alsopp's shoulder. "I am mighty near one," he says.

Act II, Scene 2: Mrs. Sprigg's boarding house, Washington, D.C., February 1847

Abe and his wife Mary are finishing breakfast. Their son Robert, age four, and baby Eddie are with them. Most families of Congress members from distant states like Illinois stay at home, but Mary, like her husband, is ambitious. She is interested in politics. James K. Polk is the president. The war in Mexico is underway. Slavery, of course, looms large and so many of their "messmates" are anti-slavery, Sprigg's is known as "Abolition House."

Lincoln walks out of Abolition House and towards the Capitol. The streets are muddy. He walks past pedestals for statues yet to come, pediments with friezes yet uncarved. He climbs the steps to the Capitol, its dome, like the nation, still being built.

We see him take his seat. It far from that of John Quincy Adams. This is a metaphor. Lincoln is a moderate, a listener to all sides. Cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason is his support. Adams has dedicated his final decades to openly, relentlessly fighting slavery. His age is the only thing that keeps some Southerner from killing him.

Lincoln is at his desk when John Quincy Adams begins to slide to the floor. Someone shouts "Mr. Adams is dying!" People race to the former president's desk. "This is the end of earth," Adams says, "but I am composed." Congressman Lincoln understands. Adams saw what his duty was and spent his life doing it. No one could hope for more.

Act II, Scene 4: The Cooper Institute, New York City, February 1860

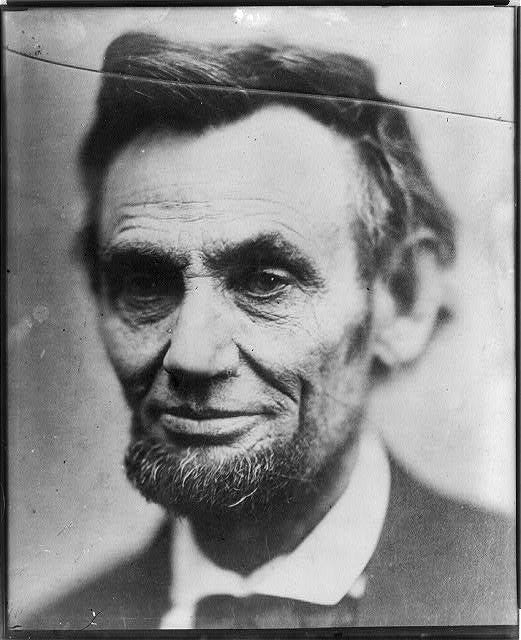

The lecture hall is large. People brush snow off their coats as they take their seats. Abraham Lincoln is on stage. He wears a rumpled black suit. His cheekbones are sharp and his eyes, under bushy brows, are as deeply grave as in the photo Matthew Brady made of him earlier today. Yet they can, in an instant, glint with infectious wit.

Lincoln is being previewed as a presidential candidate. He's ill-prepared for the job. The highest office he has ever held is his single term in the House. But the Republican party's leading light, William Seward, has sunk his own chances by saying there is a "higher law" than the Constitution. He is now considered an abolitionist. In his own speech, Lincoln takes care to base his argument strictly on the nation's founding documents.

He speaks steadily, building a case with pure logic, point by point. His language is simple and unadorned. But somehow his tones, his gestures, the occasional flash of mirth, bring the crowd to its feet. People are surprised to be electrified.

He tells them the South will never be satisfied. They now argue that slavery is, in the words of John Calhoun, "a positive good." They say slavery is sanctioned by God. The Missouri Compromise was not enough for them, he says. The Compromise of 1850 was not enough. Dred Scott was not enough. "The question recurs," he says, "what will satisfy them? . . . This, and this only: cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right."

Act III, Scene 1: The Willard Hotel, February, 1861

Lincoln paces. His inauguration is days away. The election was hair-raising. He won the presidency with 39.8% of the popular vote, but afterward, people expected some kind of attempt to stop the counting of the votes. General Winfield Scott declared that anyone who tried "to obstruct or interfere with the lawful count" would be "lashed to the muzzle of a twelve-pounder and fired out a window of the Capitol." But the vice president John Breckenridge, a known Southern sympathizer, did his duty and declared Lincoln president.

All through this secession winter, Abe has been urged to compromise with seceding states. He declines. He has drafted an inaugural speech in which he says he won't strike first, but is resolved to hold the forts now besieged in secessionist states.

He too is besieged--by office-seekers and politicians eager to bend his ear. Enter Senator Charles Sumner, one of the politicians. They have never met, but Lincoln knows who he is. One of the era's most revered statesmen, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, his brutal beating by Preston Brooks has made him a hero of the North.

As Sumner walks in, Abe is surprised to see that the Senator is as tall and gawky as he is. Delighted, he suggests they stand back to back, to see who is taller.

Sumner, a Boston Brahmin, a graduate of Harvard Law, finds this suggestion absurd. He eyes this frontier redneck and despairs for his country. On the brink of civil war, this bumpkin is commander-in-chief? Sumner is not alone. Many accomplished statesmen are distressed by Lincoln's apparent unfitness. Abe's lack of polish will only be polished to a gleam after his death. The qualities that form his legend--the ungainliness, the homespun speech, the ill-fitting suits and social cluelessness--were faults in his own time. He succeeded not because people learned to love his faults, but because he emptied the office of his own personality. He took his ego out of it, inhabiting the Executive not as an individual, but as an ideal.

Still, Charles Sumner's education and experience have not been for naught. He politely refuses to match measurements with the president-elect. It is time, he tells Lincoln, to unite our fronts, not our backs.

And then he tells Abe about a legal doctrine he believes in, as did old John Quincy Adams: that the president, in wartime, has the power to free the slaves.

Act III, Scene 3: President Lincoln's office in the White House. April 1861.

The war is on. When President Lincoln sent a ship to resupply the troops of Fort Sumter with food, South Carolina's militia fired on the fort and the flag. The North's ire is roused. The president has called for 75,000 troops.

His advisors are around him, discussing the war. The advisors feel confident of a quick Union victory. The North has the factories, someone says. The North has the banks. What are the people of the South? A bunch of farmers too lazy to hoe their own rows, grown fat off the labor of slaves.

"We must not forget," the president chides them, "that the people of the seceded states, like those of the loyal ones, are American citizens, with essentially the same characteristics and powers."

Act III, Scene 3: President Lincoln's office in the White House. July 1861.

Lincoln and General Scott are exhausted. They have stayed up all night, working on a plan. The Union has just suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of Bull Run. It is dawning on them that the war is not going to be as straightforward as they thought.

The new plan, nine points Lincoln scrawled in pencil on a scrap of paper, lies on the desk. Lincoln stands at the window. Outside, bedraggled Union troops are straggling into town. Some are wounded, some have vacant stares. Carts are rolling in on which wounded men writhe in pain. Other carts come with piles of corpses.

Enter a Republican functionary. "John," the president says, "if hell is not any more than this, it has no terror for me."

Act IV, Scene 2: President Lincoln's office in the White House. January 1, 1863.

Enter Secretary of State Seward and his son Frederick. Frederick is carrying a large portfolio. It contains the Emancipation Proclamation. Cabinet members and President Lincoln watch as he lays the parchment on the desk. Abe takes up his pen and dips it in ink. But then he hesitates.

"I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper," he tells them. "But I have been receiving calls and shaking hands since nine o'clock this morning, till my arm is stiff and numb. Now this signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled they will say 'he had some compunctions.'"

Then he slowly and carefully signs the document. The signature is clear and solid. Everyone laughs at his worries. It's easier than contemplating what they've done, what is still to do.

Act IV, Scene 4: The White House private apartments, June, 1863.

President Lincoln enters his wife's room. Mary Todd Lincoln is being fitted by her dressmaker and friend, Elizabeth Keckley. Born a slave in Virginia, Lizbeth, as Mary calls her, bought her own freedom at age 30 and built a dressmaking business. She knows the Lincoln family well. She was with them when their third son, Willie, died of typhus, less than a year into Abe's presidency. Mary nearly lost her mind.

Both Lincolns have been sad ever since. But today Elizabeth thinks the president looks even gloomier than usual. His step is plodding, his face worn. The war is not going well. The fighting has been brutal since the Emancipation Proclamation. The Confederates beat the Union at Chancellorsville in May, and at Winchester in June.

The president throws himself listlessly on the couch.

"Where have you been, father?" Mary asks . They call each other mother and father.

"To the War Department." He sounds almost sullen.

"Any news?"

"Yes, plenty of news, but no good news. It is dark, dark, everywhere."

Abe reaches for a bible, and begins to read. They leave him be. After fifteen minutes, Elizabeth notices that his face is calmer, almost cheerful. She thinks she sees signs of hope, of resolution. Curious to know which text could work on him so, she pretends she has lost something and slips behind the couch to look over his shoulder. He is reading The Book of Job.

Act V, Scene 1. The east front of the Capitol. March 4, 1865.

The day is gloomy. Dark clouds loom. Frederick Douglass joins a throng flowing up muddy streets to the Capitol for the inauguration. He senses murder in the air.

At long last victory seems at hand. With Ulysses S. Grant in command of the Army, Union victories are mounting. General Sherman has taken Atlanta, then slashed his way to the sea.

Douglass keeps an eye on Lincoln's carriage as it makes its way to the Capitol. He finds a spot close enough to the east portico for Lincoln to see him. They have met at least twice. Abe spies Frederick in the crowd and points him out to his new vice president, Andrew Johnson. Johnson looks at Douglass with distaste, then fakes a friendly face. Douglass knows in that moment that the vice president is no friend to his people.

When Lincoln steps forward to speak, the clouds part and a beam of sunlight breaks through. His address is short. Lincoln's own eloquence comes from simplicity. When he wants grandeur, he reaches for Shakespeare or the King James. As now, when he closes: "Fondly do we hope--fervently do we pray--that this mighty scourge of war shall soon pass away. Yet if God wills it continue until all the wealth piled by the bond-man's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until each drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid for by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

Abe expects some people won't like this. People don't like to be told God is angry with them. Later, at his inaugural reception, the president asks Douglass what he thought of his speech. He says he values no man's opinion more. "Mr. Lincoln," Frederick Douglas tells him, "it was a sacred effort."

"I am glad you liked it," the president says.

Act V, Scene 3. General Grant's tent, City Point. March, 1865.

Richmond is expected to fall any day now. The president wants to be there for it. He and General Grant sit at a campfire. Abe waves the smoke away with a hand. Grant offers food but Lincoln declines. His stomach is upset from some bad drinking water.

He notices three stray kittens, mewing pitiably. They have lost their mother. The president picks them up, pets them. "Don't cry," he tells them. "You'll be taken care of." 600,000 men have died and the president wants to help three kittens. He asks an officer to be sure the "motherless waifs" are treated kindly. Give them milk, he says. The colonel agrees to see to it. Only then does Lincoln put the kittens down and go back to his boat, to await the end of the war.

Act V, Scene 6: Ford's Theatre, evening, April 1865.

The play is a silly one. It's a comedy about what ensues when country bumpkin Americans bump up against English aristocrats. Brits love this theme, and oddly, Americans do too. The dialogue is good enough that the young guard assigned to the president, John Parker, gets hooked. From the back of the presidential box he can hear the actors, but he can't see them. He slips out and finds an empty seat to watch the performance.

In his box, President Lincoln is tired. It has been a long day. He doesn't notice that Parker is gone. He doesn't notice when the door handle behind him turns. He takes Mary's hand.

Share this post